Smart Contracts, Platforms and Intermediaries

Crypto Economics as a mixed human-machine system fueled by economic incentivisation mechanisms is an alternative to monolithic platforms.

Smart Contracts, Platforms

and Intermediaries

Taken from Moderat — Bad Kingdom

Abstract

Crypto Economics as a mixed human-machine system that is fueled by economic incentivisation mechanisms displays an interesting approach to an organizational problem, that is currently solved through a monolithic platform approach. The new model carries its own governance problems, when it comes to establishing a clear separation of concerns between the meaning and the processing of data. Economic incentives as a base line coordination mechanism within mixed human machine systems have their limits with regard to outside information. Diverging consensus groups may however be able to fork off and restabilize, if certain conditions are met.

Introduction

One of the more interesting insights produced by research in Bitcoin and the contemporary Cryptoverse, is concerned with our traditional notion of internet platforms. Whereas much of the discussion in the blockchain community still focuses on the varying degrees of (de)centralization at the computational layer, the economic and organizational implications are just as interesting.

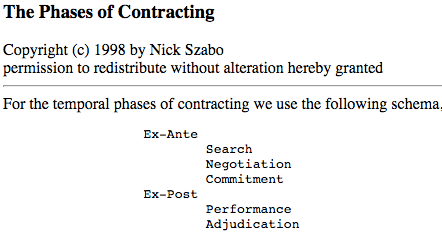

Looking at current-day internet platforms through the lens of contract, especially at platforms concerned with the trading of goods and services in horizontal networks of buyers and sellers, we can differentiate two phases of contracting between those economic actors: the pre and the post contractual phase.

Nick Szabo’s temporal model of contracting, derived from standard economic models

Transaction cost economics tells us, that each of those activities entails certain costs. The economic role of a platform is to reduce each of those expenses as far as possible. Today, platforms are based on a monolithic approach, that can be described as a full integration: in order to enjoy a platform’s network of users willing to engage in trade, one has to buy into the governance of both the pre and the post contractual phase on the platform’s terms. This gives the platform provider, the firm, an arguably unproportional amount of influence over broad ranges of economic activities.

In effect, the platform model of today proves increasingly incompatible with some fundamental values modern societies hold dear, such as freedom of speech and the right to privacy. In case of platforms focused on economic trade, the very notions of private autonomy and freedom of contract are called into question.

Since the invention of Bitcoin and the Blockchain, there is a new organizational model of how to reduce transaction costs effectively, while yielding vastly different results with regards to the protection of the fundamental rights affected by the deep diffusion of technology in modern day society.

Splitting the atom

A fundamental assumption behind Szabo’s idea of smart contracts, is a plurality of intermediaries for coordination tasks such as search and negotiation or performance and settlement.

Smart contracts often involve trusted third parties, exemplified by an intermediary, who is involved in the performance, and an adjudicator, who is invoked to resolve disputes arising out of performance (or lack thereof). Intermediaries can operate during search, negotiation, commitment, and/or performance.

Today, however, nearly twenty years later, the development of the internet as a medium of significant economic trade appears to have turned out differently: instead of a multitude of competing service providers for the different phases of contracting, all contractual phases happen within the confines of one monolithic platform. A platform in the hands of a private firm, governing both through technical means (software and services) and legal means (terms of service).

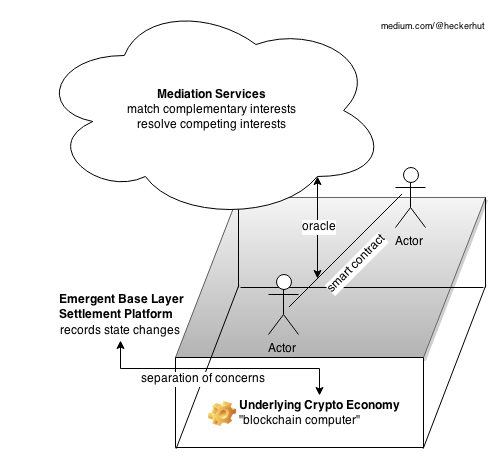

In the Blockchain model, the notion of mediation services in both the pre and post contractual phase is split off from the idea of a public settlement layer on which changes in ownership of assets and other fundamental state variables are recorded. As a result, there are less opportunities for any of the service providers involved in the different phases of contracting to create the typical lock-in effects that we can observe with today’s platforms.

The blockchain model accomplishes this functional reconstruction of existing techno-economic infrastructure with an impressive feat: it creates a sort of secondary economy around the provision of computational resources. That is, the technical peer-to-peer protocol that coordinates the construction of a blockchain-type computer provides economic incentives for people to provide resources for said infrastructure. Those incentives are in turn disconnected from the semantic meaning of the data those resources are used to process (separation of concerns).

The Blockchain Model

As shown in the picture, mediation services interact with the Settlement Layer, but they don’t “own it”, i.e. it is not integrated in their infrastructure and therefore accessible to everyone else. In effect, it creates an open environment for competition to blossom.

There might still be lock in effects in phases such as search because of classical network effects. But the pace of those network effects cannot be forced through technological lock-in effects as its done today. Moreover, switching costs are minimal between providers of mediation services because data portability is mostly a non-issue: the data is kept in publicly accessible blockchain databases. Most interestingly, this data may also include reputation and other forms of social capital.

Separation of Concerns

Let’s have a closer look at what can be said to be the magical effect of blockchains, that got everyone hooked. It is what I refer to in this post as a separation of concerns. In Bitcoin it is referred to as fungibility. It is the idea, that the semantics of a transaction, i.e. the humanly-associated meaning of data, is disconnected from the processing of the data. This separation is the making and breaking of a functioning blockchain-based ecosystem.

Adam Back talked about this problem in terms of fungibility in his LTB episode. In case of a monetary system, the separation of concerns afforded by a crypto economic incentive regime guarantees that each bitcoin is worth exactly 1 bitcoin, no more and no less. Or in other words: there is no possible reason why you wouldn’t exchange a specific set of utxos for another set of utxos if the cumulative output amount were exactly the same.[1]

That problems can in fact arise is an undisputed wisdom in the Bitcoin community. Andreas Antonopoulos and Adam Back talked about this in terms of the usefulness of zero-knowledge proof systems, which would ensure perfect fungibility on a mathematical level. Back also supports weaker measures such as dark wallets and laundry services before working proof systems with the desired characteristics are in a useably state of development. The discussion shows that a working separation of concerns is the achilles heel of a functioning blockchain ecosystem.

In case of a general purpose crypto economic computing platform such as Ethereum, the situation becomes even more delicate. Besides the fungibility problem with regard to the platform’s base layer currency, complex techno-economic constructs (so-called ‘smart contracts’ or better ‘software agents’[3]) process incoming data in form of transactions and spit out data — in form of transactions. Those transactions have to go through the crypto economic underbody displayed in the picture above. Compared to a simple monetary system, there is an even bigger variety of potential reasons why the separation of concerns may break down and the semantics of a transaction may suddenly become relevant to those investing computational resources into the maintenance of the Ethereum Settlement Platform.

Grim’s Trigger and Consensus Pooling

The separation of concerns between the meaning and the processing of data can also be described as a causal closure, i.e. a boundary across which information does not, or only very controllably, travel. Interestingly, in case of the Blockchain model, the boundary is not fully technological in nature, i.e. sealed off through a digital access control mechanism, but is arguably a new form of heteromation, i.e. a mixed human-machine process.

In effect, the separation of concerns is constructed through an integration of humans and machines by means of an economic incentive regime. The involvement of humans, however, always comes at a cost, if information access and control is at stake. The boundary that defines the separation of concerns is weak, when information is accessible to humans and gets mixed up with other information, external to the crypto economic closure of the Settlement Platform.[4]

Vitalik Buterin gives us two ways to look at this problem more closely. One is the game theoretic strategy called Grim’s Trigger, the other the concept of Multichains.

Grim’s Trigger

In terms of the Blockchain’s crypto economic model, Grim’s Trigger stands for the fundamental incentive of anyone who has some form of ‘buy in’ into the functioning of the crypto economic machine to not undermine its working condition by attacking it in some unaccounted way. The motivation being, that if such an attack succeeded, the overall situation would get worse for everyone, including the attacker and nothing would have been won.

It is a bold claim and there are certainly scenarios where Grim’s Trigger is not a relevant consideration for potential attackers. Such would be the case, e.g. when a substantial amount of time lies between the rewards of an attack and the upcoming punishment. This may explain the current state of regulation through economic incentive regimes in the field of environmental protection.

Grim’s Trigger serves us, however, as a measurement tool to examine along which lines the techno-economic closure of a Blockchain system may break.

Consensus Pools and Strong Subjectivity

**Where Grim’s Trigger fails as a motivational tool to keep players faithful, an **antifragile defense mechanism may be built into Blockchain-based systems, thanks to the peer-to-peer nature of the underlying technology stack. The mechanism in question has been talked about in the form of consensus pools and strong subjectivity[5] and may be considered a sort of relief valve for dissenting groups.

A general purpose crypto economic network may be able to account for consensus plurality, i.e. the co-existence of multiple groups with related but competing histories enshrined in their collectively maintained virtual state machines. Sidechains are essentially just another variation of the same idea, implemented across different protocols. In the event of a historical fork within an existing consensus group, market exchanges or merge mining may start to replace the preceding consensus-based integration of group members.

Summary

Crypto Economics as a mixed human-machine system that is fueled by economic incentivisation mechanisms displays an interesting approach to an organizational problem, that is currently solved through a monolithic platform approach. The new model carries its own governance problems, when it comes to establishing a clear separation of concerns between the meaning and the processing of data. Economic incentives as a base line coordination mechanism within mixed human machine systems have their limits with regard to outside information. Diverging consensus groups may however be able to fork off and restabilize, if certain conditions are met.

Footnotes

[1] Let’s disregard properties such as transaction age, which influence fee calculation according to standard bitcoind.

[2] In a very, very relative frame of reference :-)

[3] Smart contracts are a term coined by Nick Szabo. The Ethereum version of smart contracts is an appropriation of the original term through Vitalik Buterin, who now sort of regrets his naming decision because of a certain set of differences between his and Szabo’s concept.

[4] The closure of an economic incentive regime breaks down when new and unaccounted for incentives enter the stage.

[5] As opposed to weak subjectivity.

By Florian Glatz on May 18, 2015.

Exported from Medium on January 3, 2025.